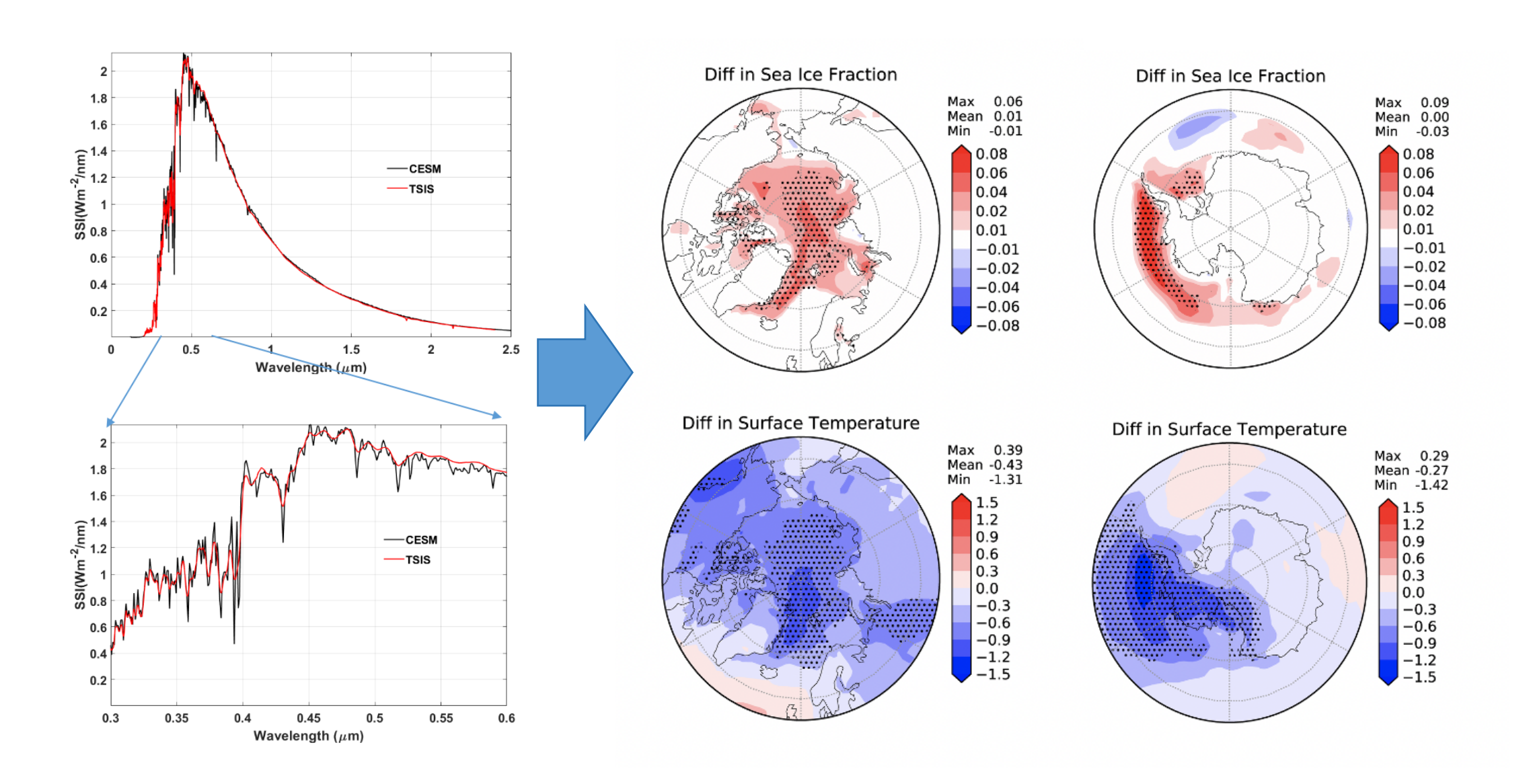

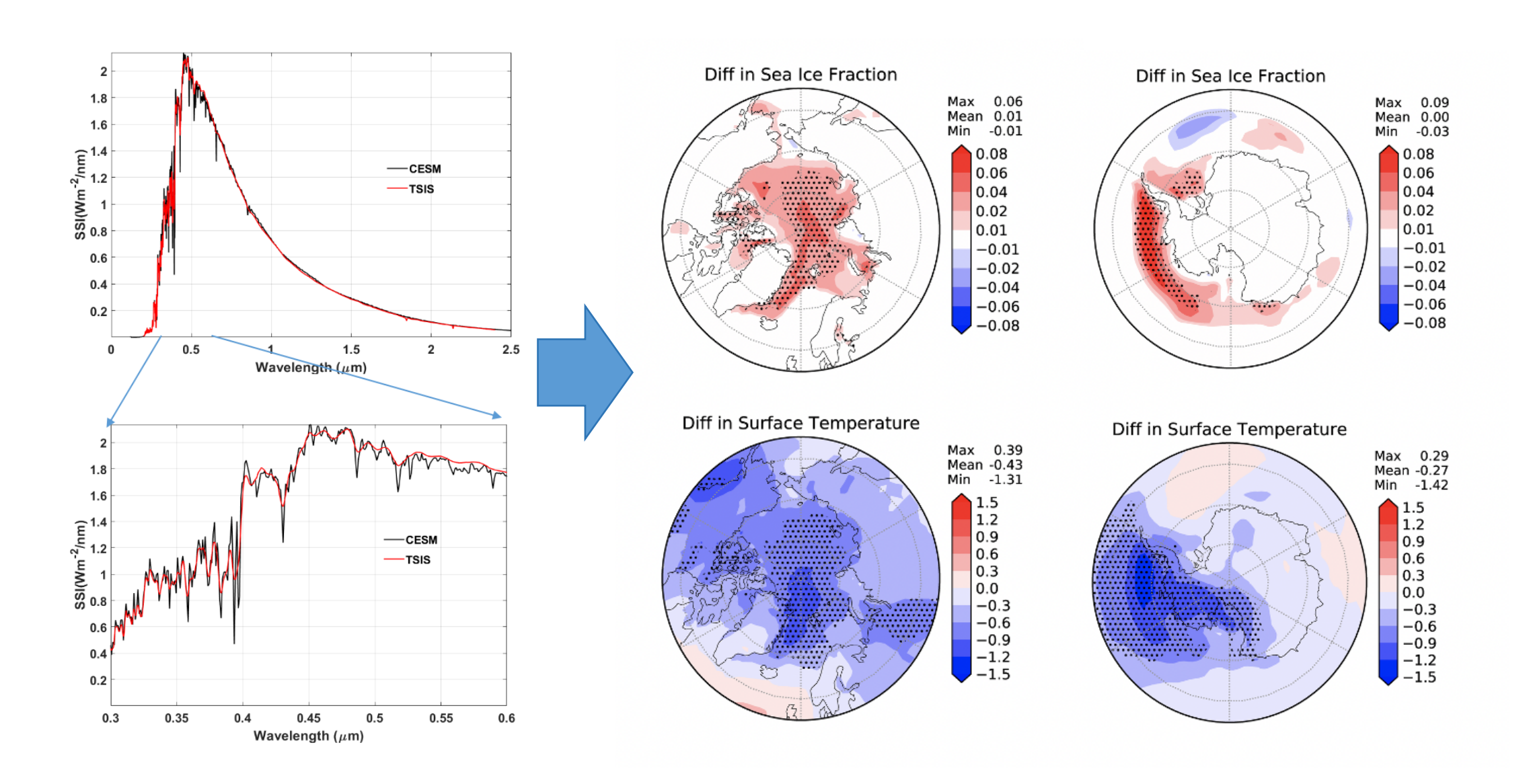

Solar spectrum’s importance to climate modeling

Observed solar spectrum significantly affects polar climate projection.

Observed solar spectrum significantly affects polar climate projection.

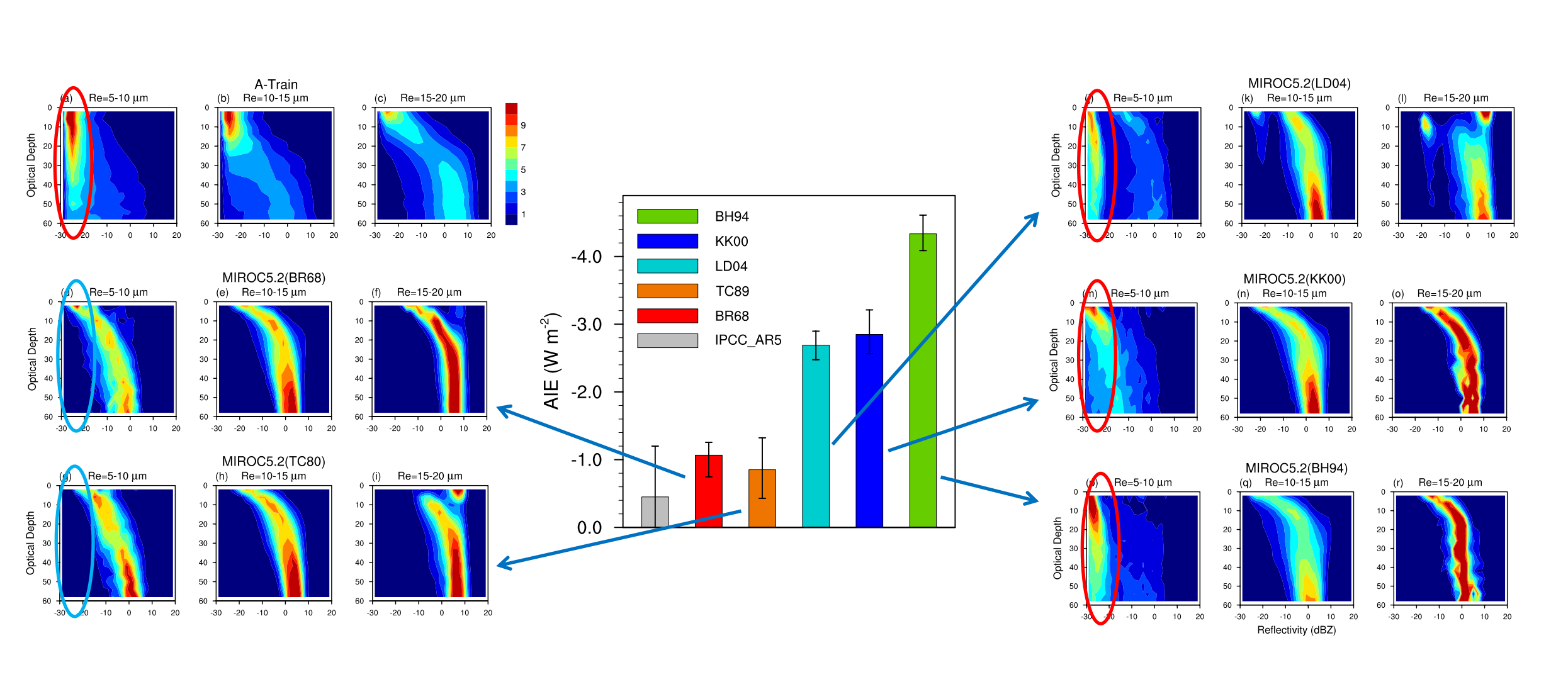

Warm-rain microphysics is key to modelling future warming.

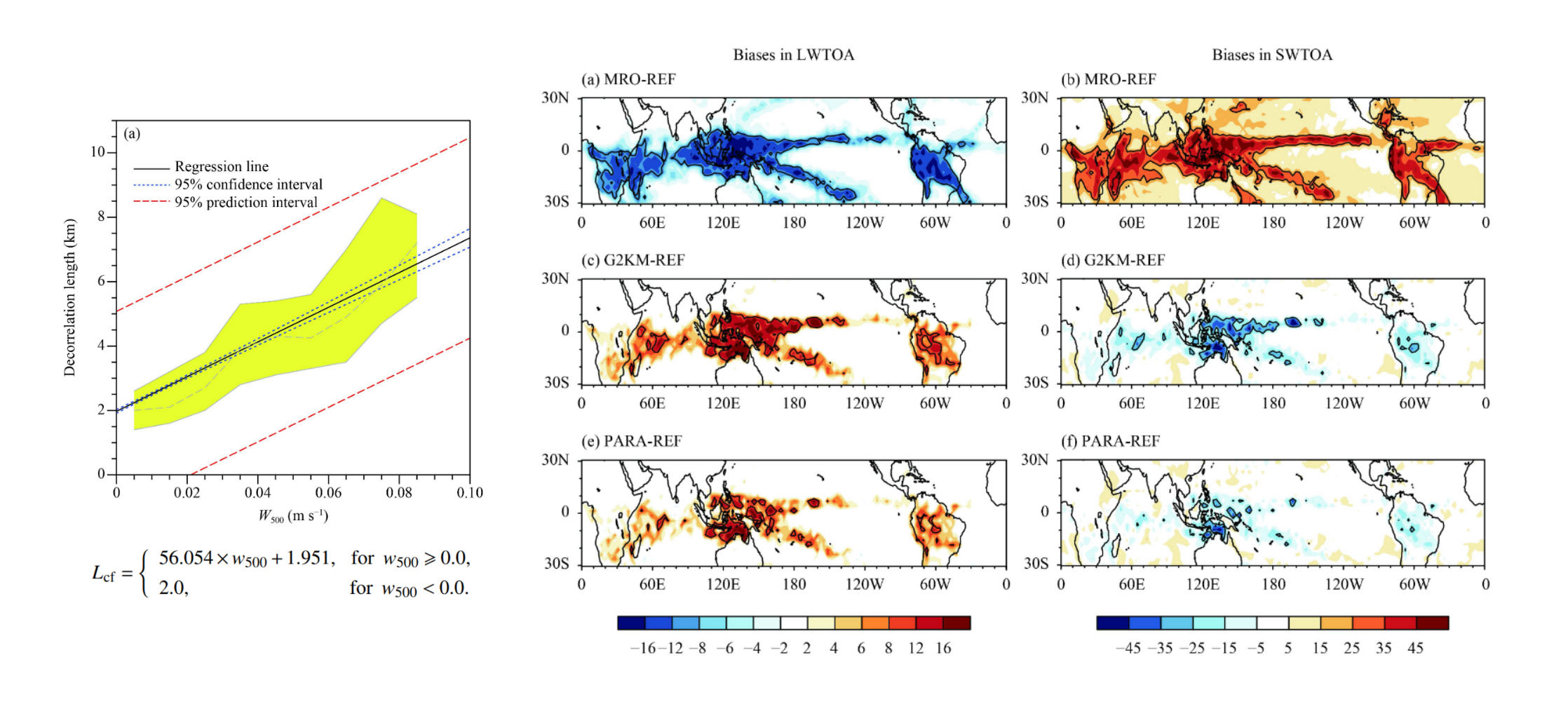

Associating cloud overlap with its dynamic environment improves radiation in GCMs.